My first two sources were both articles I discovered on the internet. The first article was by Christine Yu called "No Pain, No Gain? 5 Myths About Muscle Soreness," on Dailyburn.com and she cited several sources, which were all professionals. The second article, "Everything You Need To Know About Your Sore Muscles And Getting Relief From The Pain," was by Dr. Matthew Isner, on Bodybuilding.com.

Both articles noted, that you should experience delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), but it will be more likely to happen when you start new exercises, or if there is an increase in your training intensity and time. In both articles I read that you could experience this soreness between 12 hour up to three days after certain activities.

Image: Express Heat Therapy

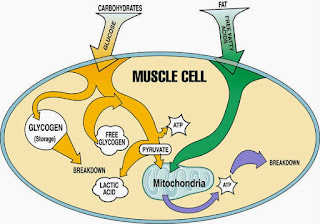

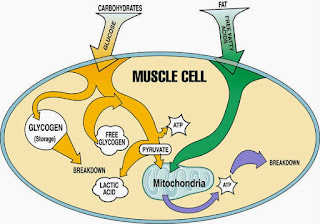

Although both authors could agree on DOMS, they might disagree on the reasoning behind it. Dr. Isner states that, "Lactic acid interferes with the actin and myosin that contract protein fibers of the muscle tissue, as well as the Glycolytic enzyme activity (the primary function of this system is to break down carbohydrates), which leads to the carbohydrates your body uses for fuel to result in lactic acid build up, leading to soreness." On the other hand, Christine Yu argues in her article that the build up of lactic acid does not result in DOMS. She mentions that during exercising, our bodies will break down molecules to get the energy we need. She states that lactic acid only happens to help our bodies pace themselves, resulting in the body cells of becoming acidic, but this only lasts up to an hour after a workout. Yu also found a study provided by Clinics in Sports Medicine, that points out the DOMS is the result of micro trauma in the muscles and surrounding tissue.

Image: Orihuela, Thomas, fitadapted.blogspot.com

Christine Yu interviewed a CSCS, NSCA-PTD, and PhD candidate, named Jon Mike. Mike expands on the difference between muscle damage and soreness. Although we might experience trauma on the muscle fibers, it is not always the exact result in muscle damage. He claims that, "some muscle trauma is needed to stimulate protein production and muscle growth." If it is an injury, you will most likely be able to tell right away, but soreness slowly appears the next day.

One thing that really surprised me, was that stretching before a workout does not help reduce DOMS, but can actually decrease your strength, stated in Christine Yu's article, founded by Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Soreness is not an effective way to measure muscle growth and adaptation because everybody is different. It leads back to a genetic component, and is all dependent on how well your body responds to pain. It is good to regularly change up your exercise routines, or even reduce your time and load of weights once in a while, and engage in recovery solutions. Solutions include, but are not limited to, massages, hot/cold showers, sleep, and an increase in your protein intake.

Image: Healthline, Healthline Media

I am curious if Dr. Isner has done research studies himself? There wasn't a whole lot in his article, and he was very brief on his citations. I'm more curious as to how your body can continue to learn new routines and keep variety in working out? Like, how does it understand the difference in new exercises? Something I don't know, is how many muscles do we have in each body part (arms, legs, etc,)? With all this being said, still being left at some confusion, I think I need to go further with my research with human biology, to expand my knowledge on the lactic acid, and find proven results.